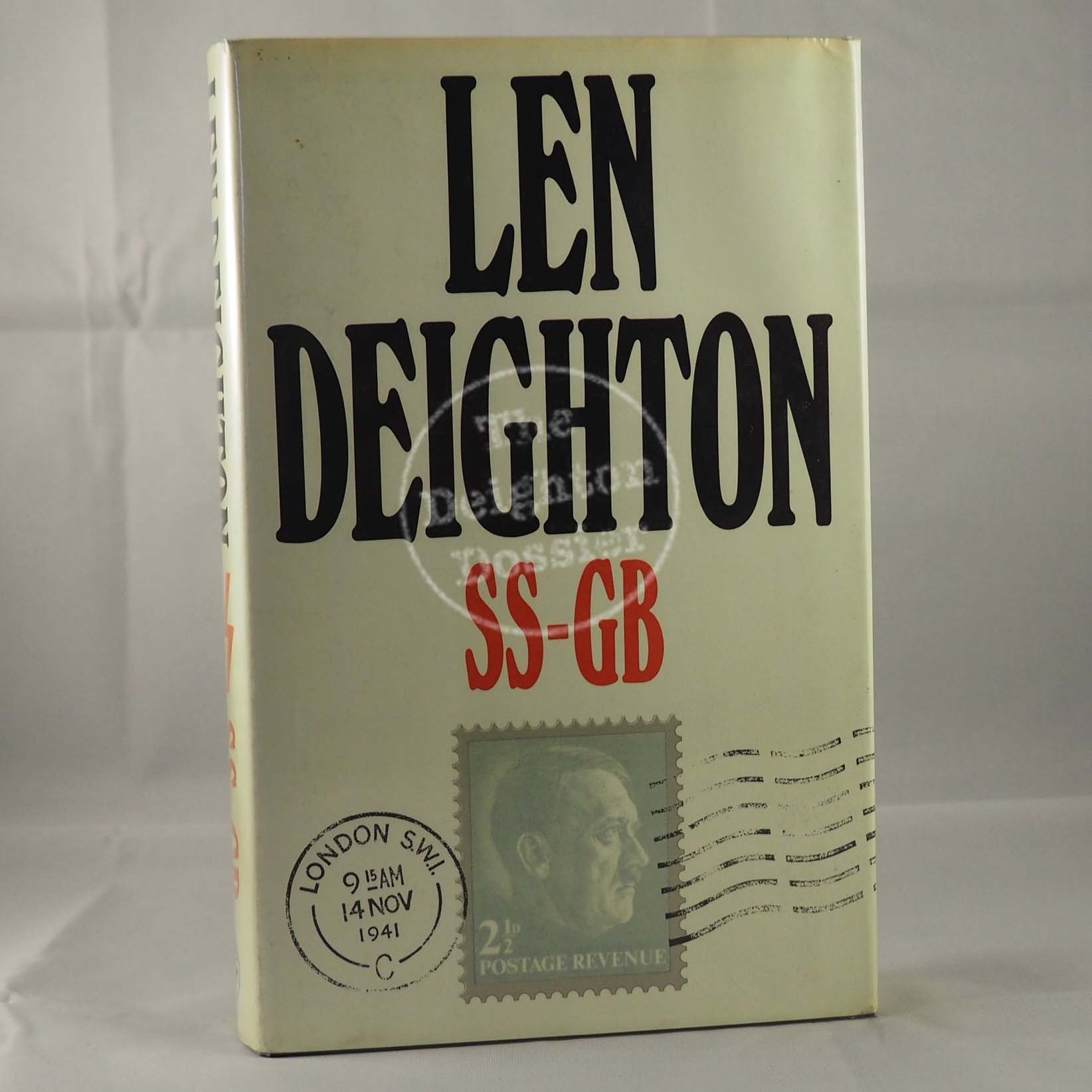

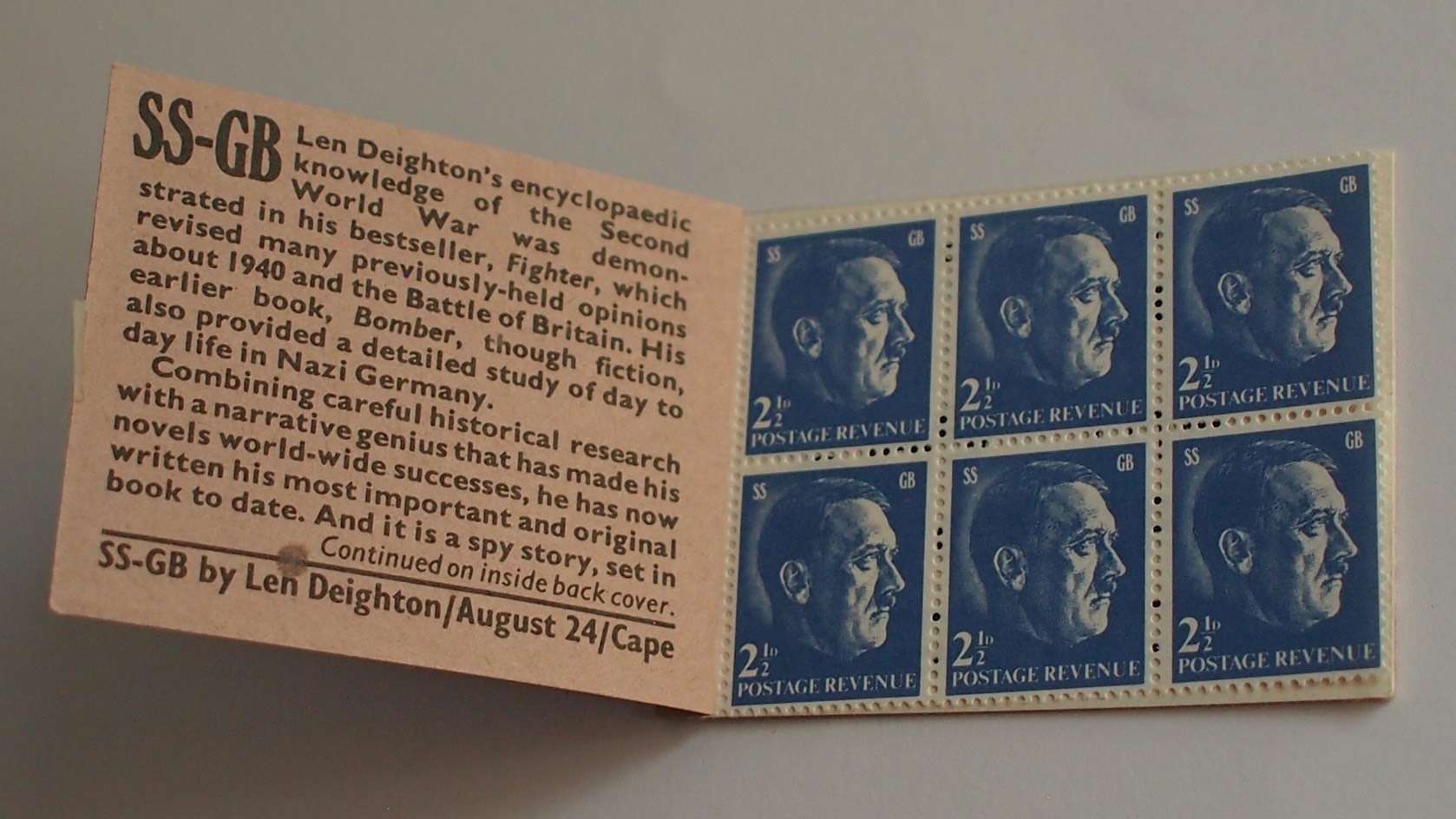

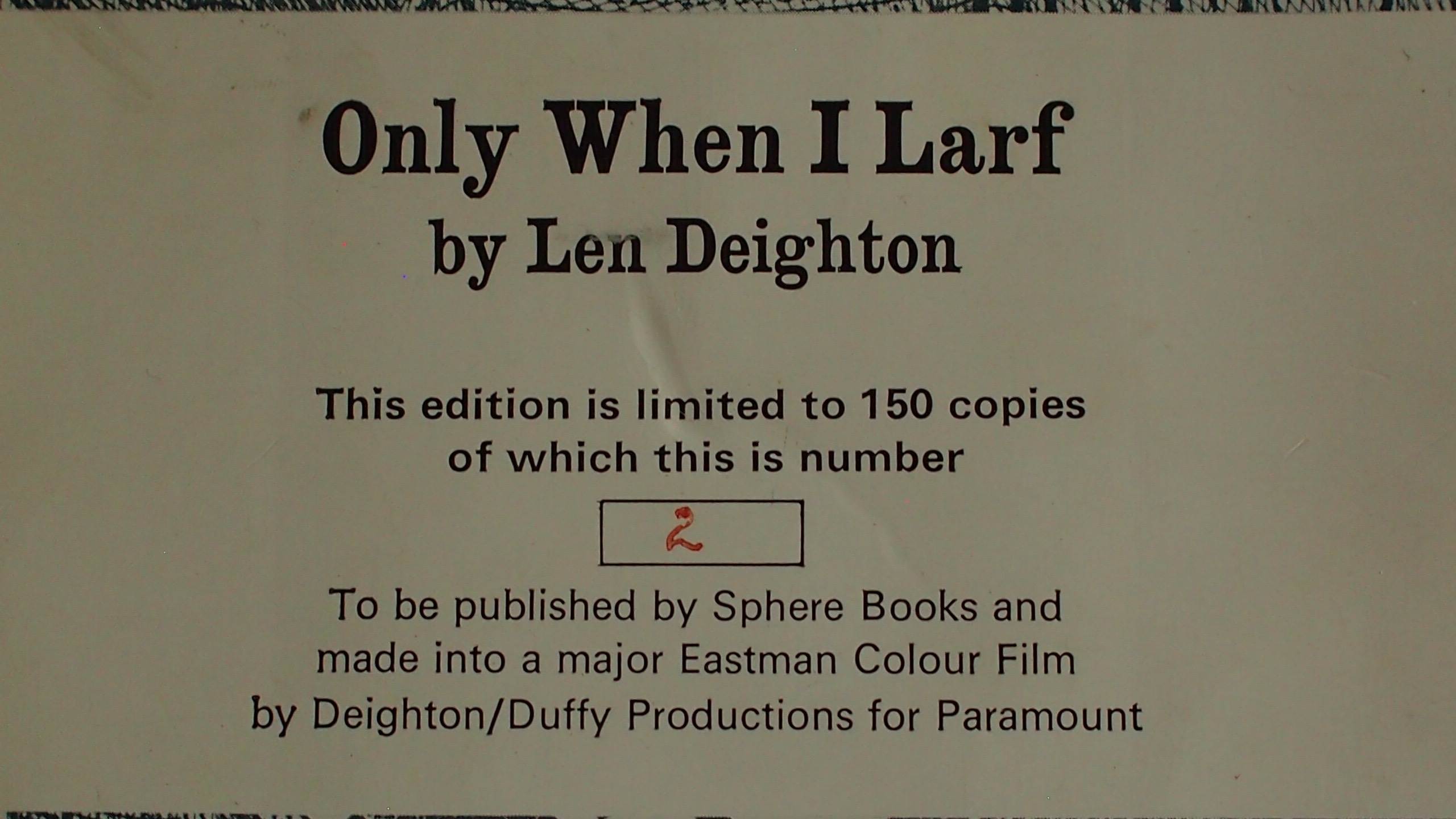

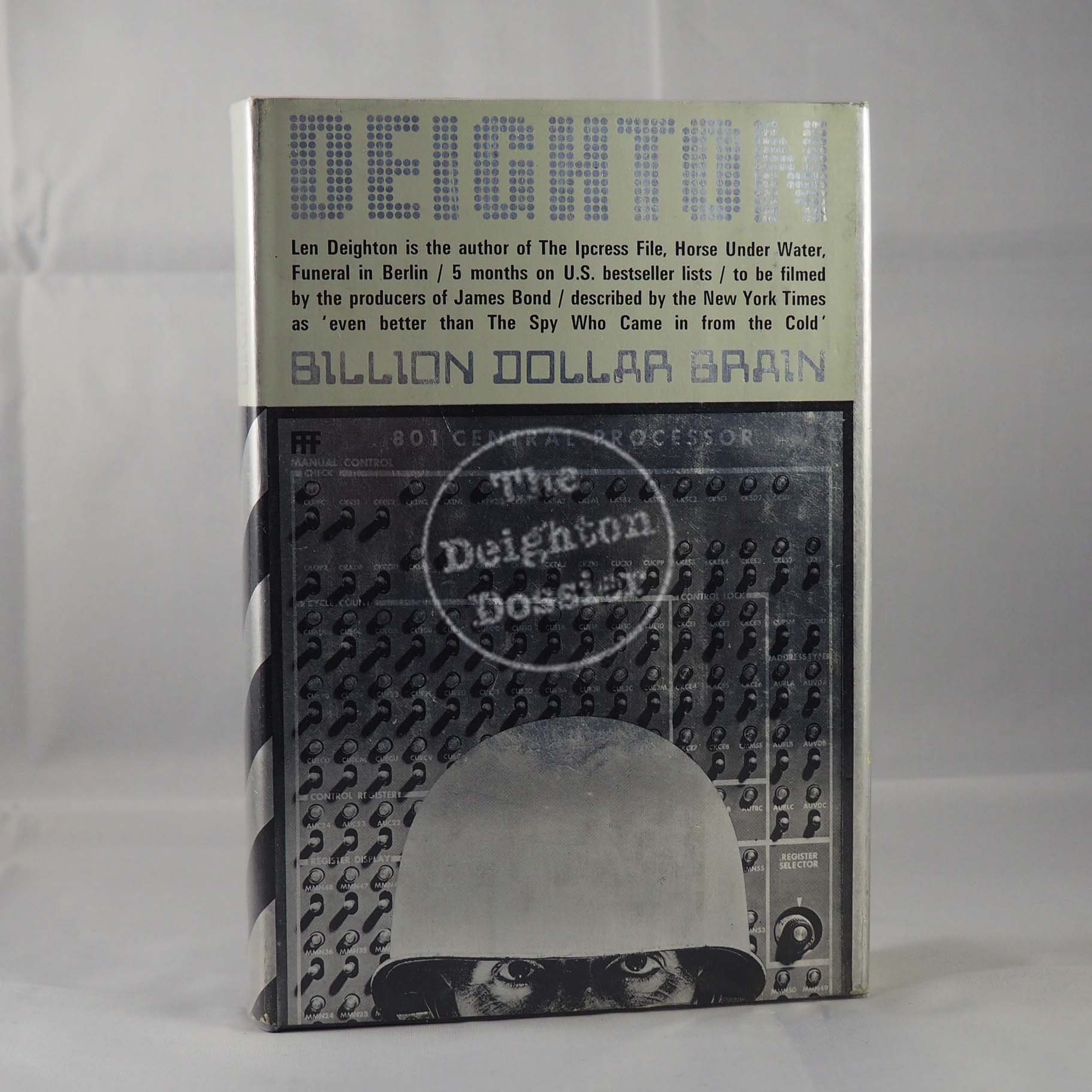

For any serious collector this is the Holy Grail. It is the rarest item traded on the open market and the most valuable: a good condition copy of this will be marketed for in the region of £2,300. With only 150 copies ever produced and few circulating on the open market, it is a challenge for any collector to hunt this down.

Its origin is in Len Deighton's efforts to secure the movie rights in the US. Sphere, run by Dick Fisher, offered to buy the paperback rights directly from Len Deighton instead of via his usual publisher Jonathan Cape. This meant establishing a basic copyright (which would embody all other rights e.g. screen, serial etc.) This had to be done quickly (hence the spiral binding rather than the proper book binding) and the number of copies was suggested by his lawyers.

Dick Fisher was a good friend of Len Deighton's and this relationship had a crucial catalytic role in generating the momentum behind one of Len's finest books. Fisher had not only been flying bombing missions with the 8th Air Force but he had been a part of the US Bombing Survey. It was a unique experience and Deighton urged him to make it into a book.

Len Deighton puts it this way:

"He thought about it but eventually said 'You write it, Len'

'How can I write it - I was never in a wartime bomber.'

'Yes,' he said. But you were bombed in London so you know how that feels - you know about airplanes; you can write it as fiction.'

'No, no' I said. But eventually that thought became 'Bomber'."

Another important relationship that came out Only When I Larf was Len's friendship with photographer Brian Duffy. Len describes it as "a long sad story, demonstrating the perils of good intentions". He first encountered Duffy at St Martins, but Duffy found the fashion world not to his liking. About three years later, after Deighton left the Royal College of Art, he saw him again. Duffy was working in a coffee bar. Deighton got him a job as assistant to Adrian Flowers. Duffy knew nothing about photography but Deighton suggested his knowledge and talent for fashion would be useful in Adrian's studio. It was.

By the time Deighton bought the screenplay rights to Oh! What a Lovely War, Duffy had left Adrian and was a successful fashion photographer working from his own studio. He wanted to be a film director and (with this as a long-term objective) asked if he could be a partner with Deighton: working in the production, and contributing money to pay for the screen play rights and rent and wages for the latter's offices in Piccadilly.

In fact it didn't turn out like that,

William Morris the agency would only represent Deighton personally as scriptwriter and producer, so the deal with Paramount for Oh! What a Lovely War was between Len Deighton and Paramount; Brian Duffy deferred contributing to the company costs and, in fact, never did so. Having decided to use the Brighton Piers for the film and seeing how it was mostly exterior shooting, it was clear filming couldn't start until Spring. So William Morris persuaded Paramount to finance Only When I Larf to carry Deighton through the winter months. His agents were very keen for him to cast David Niven but Richard Attenborough, the director, persuaded Deighton that he could play the main part better. He agreed and looking back, he saw that Niven's smooth, sophisticated and sexy way would would have given the film a too glamorous dimension, which casting Attenborough avoided.

The first shot sequences of Only When I Larf took place in New York, where Brian Duffy had a public argument with director Basil Dearden. It concerned camera set-ups but Deighton himself wasn't there and to this day isn't sure what the argument was about. Soon after returning from New York, Duffy had a row with Richard Attenborough. Duffy was hurt: he probably felt that Len Deighton was not sufficiently supportive, but he was in fact working a seven day week on the film and clearly didn't have time for such distractions.

Money is at the heart of movie-making and Deighton was solely and directly responsible to Paramount for the films. As well as that he had his staff and offices at 142 Piccadilly to pay for. Brian Duffy had no responsibilities of this sort, and no money invested in it. He was in fact a bystander, and somewhat resentful.

Thereafter, Duffy withdrew back to his photo studio and refused to come near to either Basil Dearden or Richard Attenborough, or indeed Deighton. The only time he heard from him again was when he asked for producer's credits.

So, though IMDB and most other film sources list Duffy as a producer he did, in fact, do little if no actual 'producing' at all; most of the hard graft was done by Deighton and the crew.

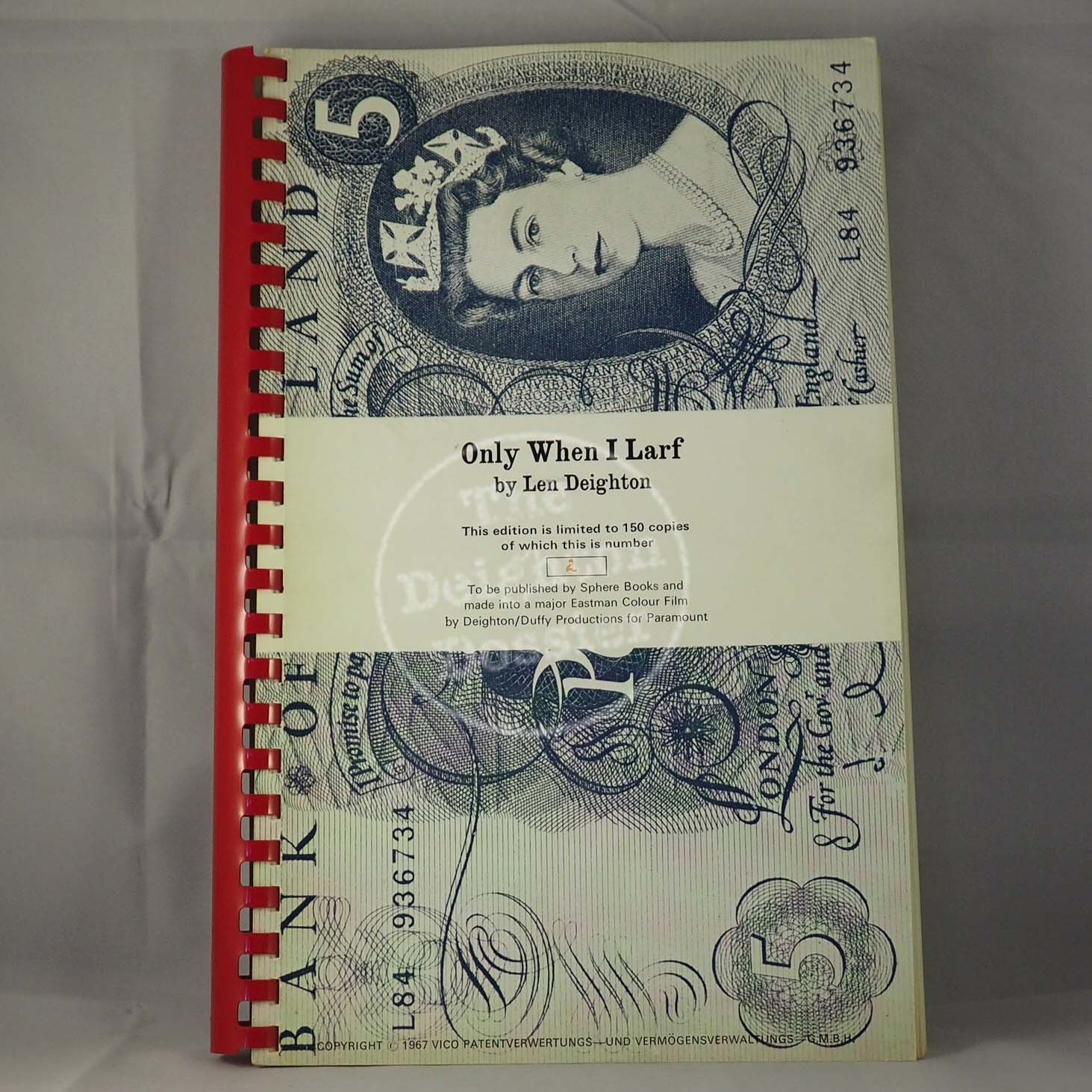

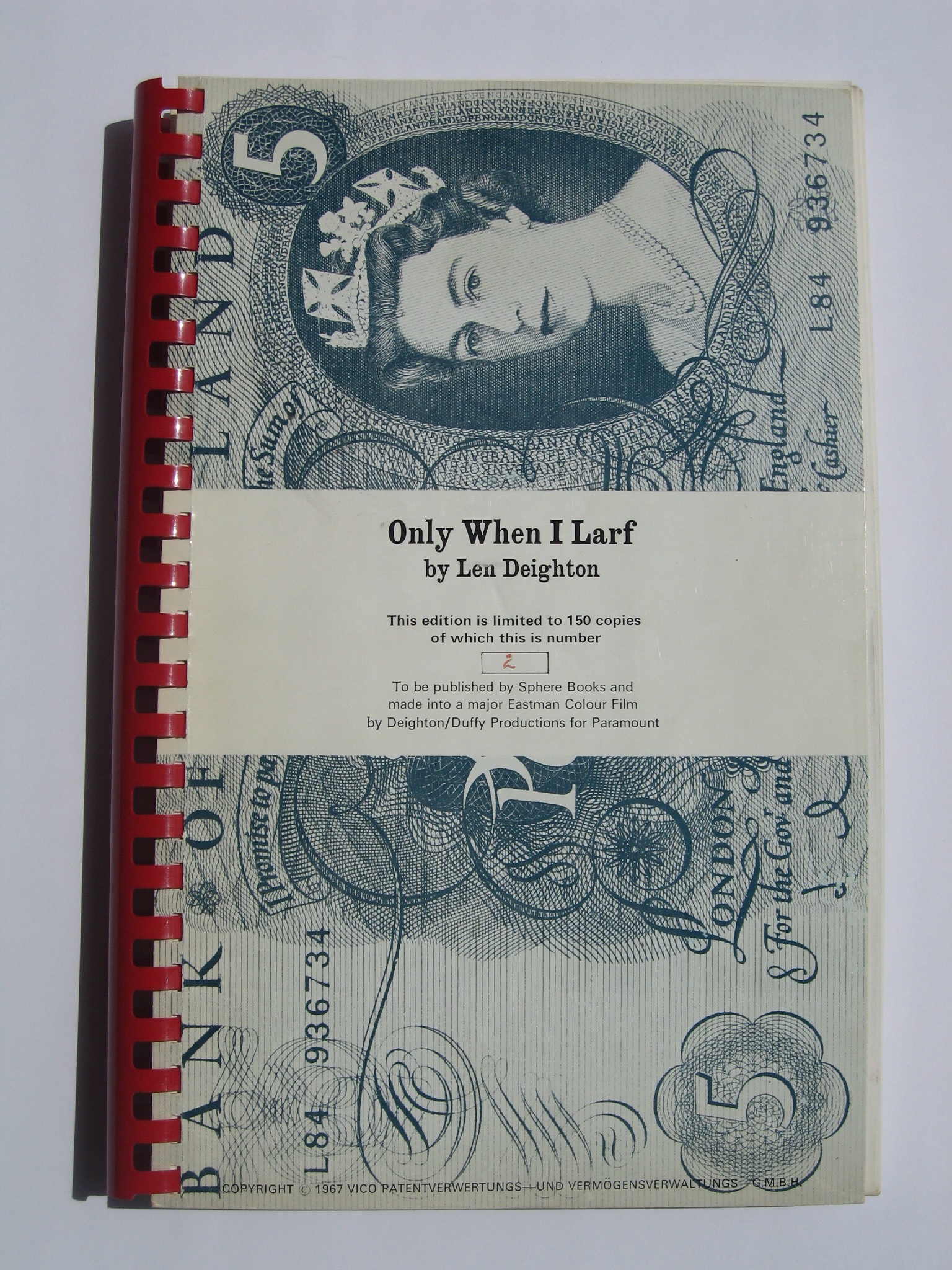

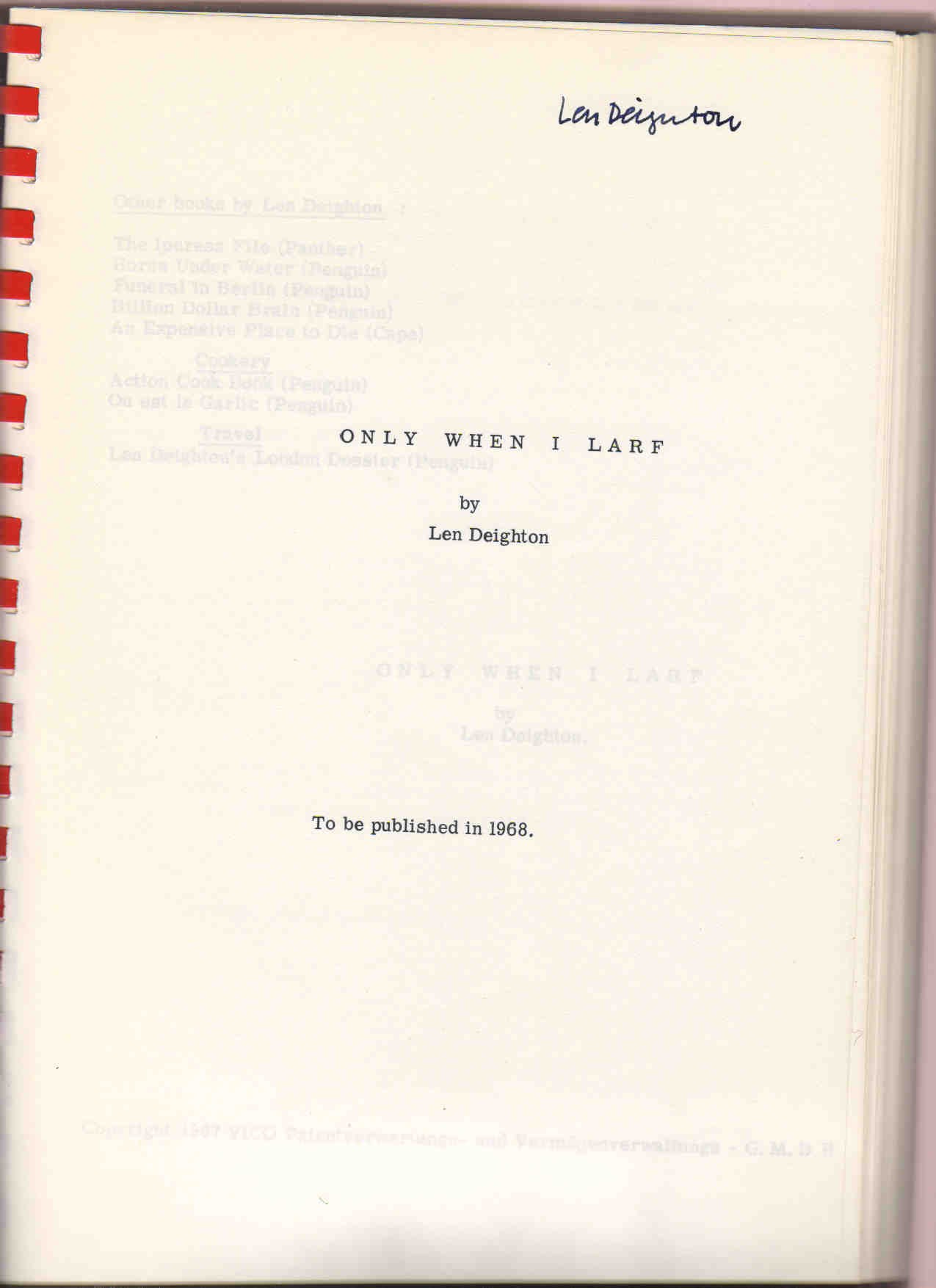

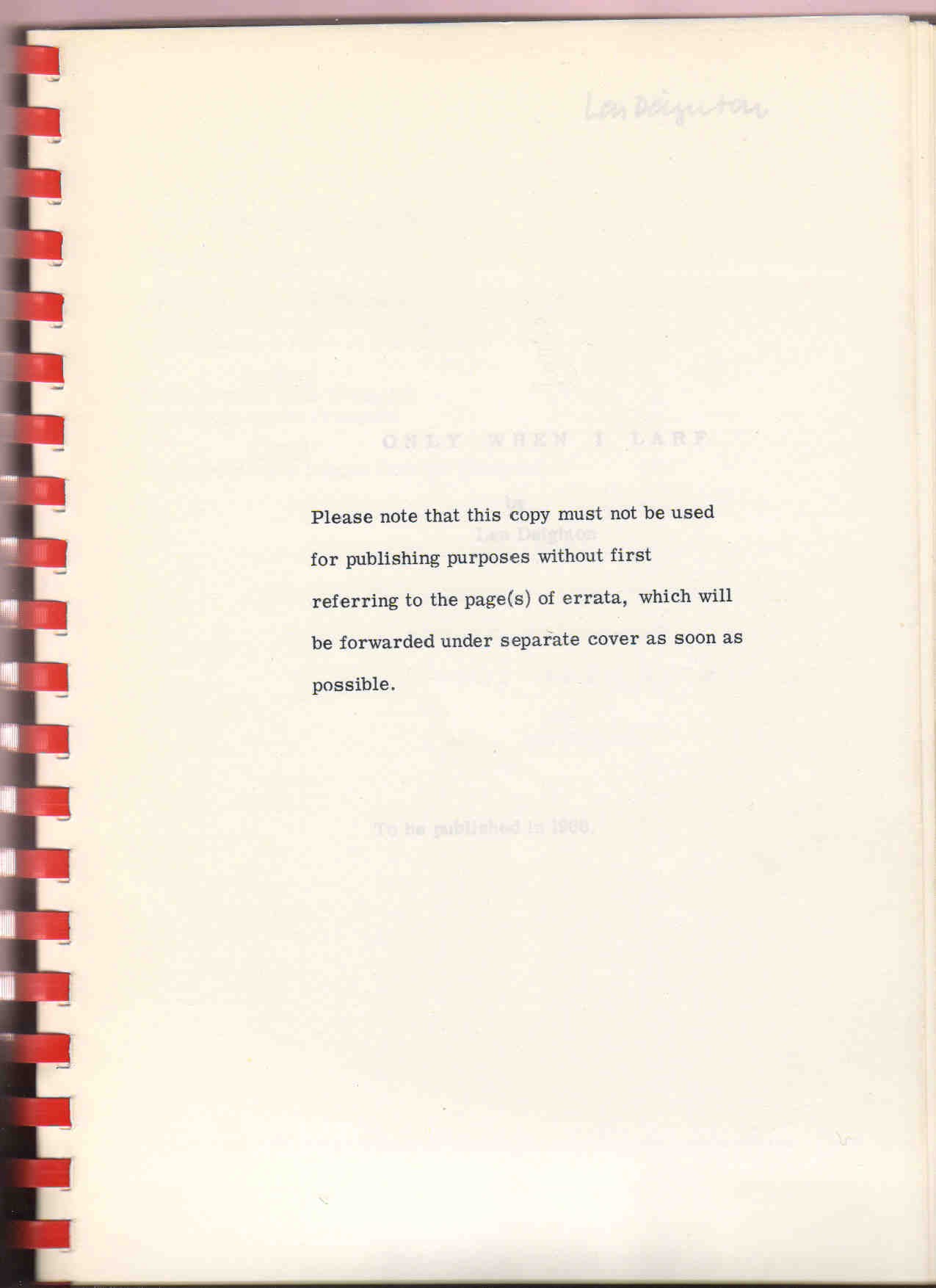

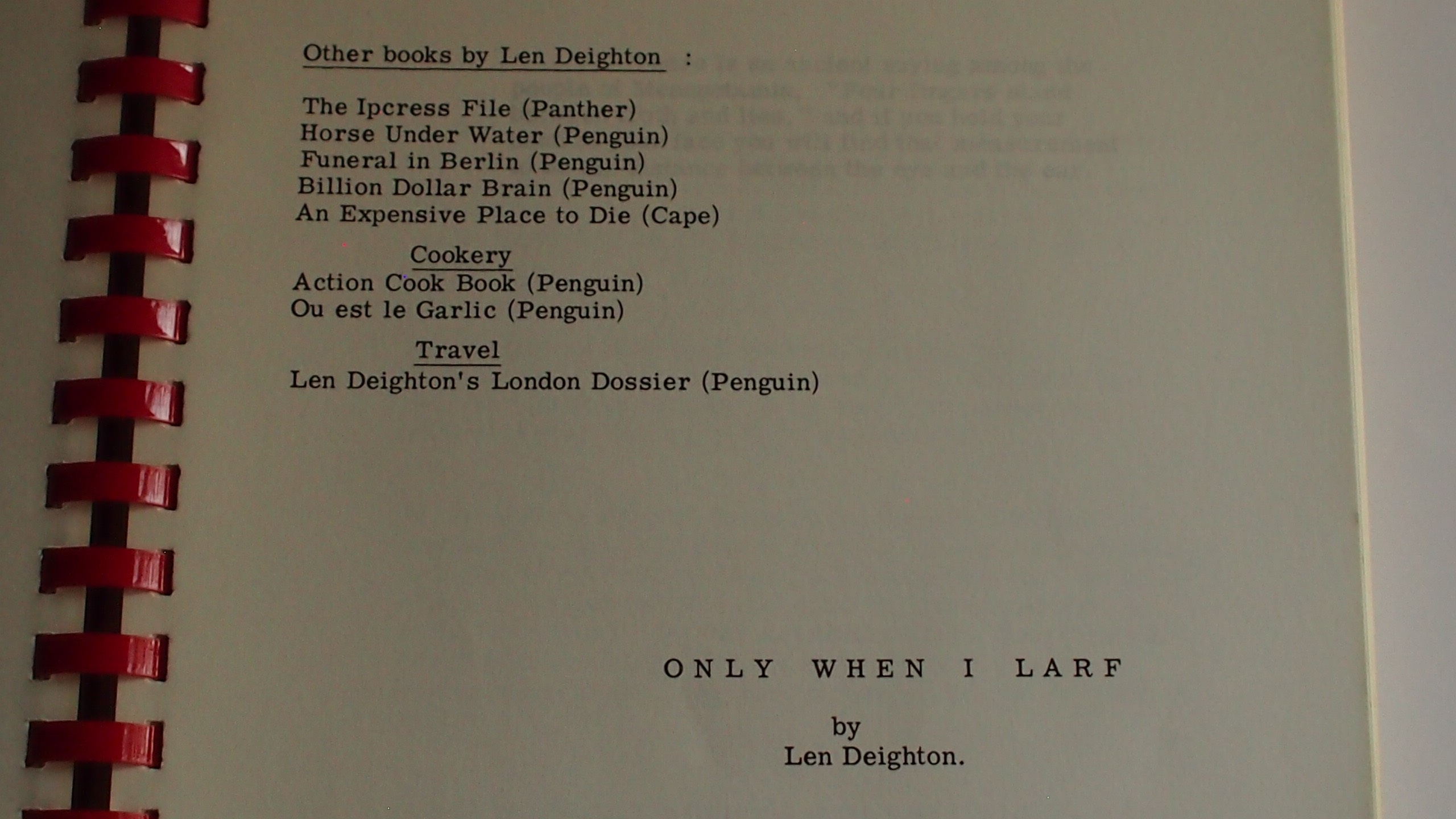

This spiral-bound book (the spiral is in various colours (red, white, blue)), is in foolscap paper size and the text is printed in Times New Roman, in a style that clearly illustrates its status as a draft, rather than a finished text. The cover is an old £5 note: the front cover with the front of the note with the Queen's head, the back cover, the back of the note. Both sides should have the centre panel with the book title, the written-in number of which edition it is and the dedication which shows the book is to be published and made into a film.

At the bottom of each cover should be the legend 'Copyright (c) 1967 Vico Patentwertungs und Vermögenswerwaltungs - G.M.B.H.' The book itself should have 176 pages.